I have previously spoken about the ontology of consciousness in my articles ‘The Ubiquity of Consciousness and the Divine Mind’ and ‘The Universe is Divine and Full of Spirits’, but since then my philosophy of mind has developed somewhat. I still agree with the main ideas in those articles, but my metaphysical commitments have shifted ever so slightly. I am still a panpsychist in that I believe consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality, but I am no longer a neutral monist. Neutral monism posits that mind and matter are made of the same underlying substance, and are thus two sides of the same coin, but I have come to believe that this is somewhat flawed. I want to explore my new idealist ontology and how it relates to phenomenology.

What is Idealism?

This change in my ontology has come primarily from reading and listening to the work of Dr Bernardo Kastrup who styles himself as an analytic idealist, but I would simply call myself an objective idealist, and am not 100% sure to what extent my views align with his. To explain idealism, it may be helpful to briefly list the three main monist theories in the philosophy of mind:

Materialism: All that exists, including the mind, is reducible to matter.

Neutral monism: Mind and matter are part of the same substance.

Idealism: All that exists, including matter, is reducible to mind.

Most historic forms of idealism are what one could call subjective idealism, which posits that reality is essentially a projection of an individual consciousness. The big problem with this however is that it doesn’t seem to be able to account for any form of consistent shared reality between distinct minds, and risks simply collapsing into solipsism.

Famously, George Berkeley thought that “to be is to be perceived” (esse est percipi), meaning that he believed that the external world has no existence outside or independent of any given mind’s perception of it. The obvious objection to this theory is the question of what happens to objects when they aren’t being perceived. For example, if you light a candle and leave the room so you are are no longer perceiving it, and then come back some time later, you’ll not only find it still lit, but you will notice that some of it has melted away. To solve this metaphysical flaw Berkeley invoked God as the omni-perciever, thereby accounting for our seemingly shared reality.

Objective idealism on the other hands affirms the existence of a shared reality that exists prior to, and independent of our subjective perception of it, but posits that matter “arises” (in an analogical sense) out of mind as an aspect of a unified universal consciousness. Here it’s helpful to point out that we should think of consciousness less of a substance and more as a field. Kastrup defines consciousness as something like “that whose excitation results in experience”. Individual minds then are dissociated “alters” of this one mind, and what we call “matter”, is simply consciousness viewed from a particular third person perspective.1 A human brain for example, is just what a human mind looks like from the outside looking in.

My mind and your mind are thus not entirely distinct, but are all participating in a limited way, in the same universal field of consciousness. By way of analogy, it may be helpful to quote from a previous article of mine:

“Imagine a whirlpool in a flowing river. The whirlpool seems to be distinct and identifiable from the river itself. It is a consistent pattern that retains a form of identity as it flows through the river. At the same time however, the water in the whirlpool is not entirely separate from, and is indeed made up of, the water of the river. The whirlpool is just a localisation of the river, such that it turns back on itself and sees itself in its own reflection. The whirlpool is a singular mind, and the river is the cosmic-consciousness.” (The Ubiquity of Consciousness and the Divine Mind)

In some sense, our individual minds are like concepts or thoughts within the universal mind, and thus they take shape based on the way these patterns of mental activity are structured. This leaves us with a form of non-dualism, in that everything is fundamentally one, even if it appears to us like there are lots of different “things” that are functioning separately on an ontological level. In actuality, distinctions between minds and objects are merely conceptual, and are contingent on the unique ways in which human consciousness perceives reality.

Inanimate objects on the other hand may be other forms of consciousness inhabiting different phenomenological realities (more on this later), but this isn’t necessarily entailed by idealism. One does not have to posit that every structure that forms out of the field of consciousness has it’s own unique and unified subjective experience. That said, I remain a panpsychist so I would be tempted to say this is indeed the case. Regardless, what we call objects are what patterns of mental activity contained within the universal mind look like extrinsically. The reason they take a particular shape, and are experienced in a particular way, is because of the way our senses work.

Take a rock for example. A rock is just a pattern of consciousness, but the reason a rock looks the way it does to us is because our senses (which could be understood as modes of experience) perceive that pattern in specific ways that “create” a certain kind of experience. A lobster who can see a much broader range of colours on the spectrum than we can would probably experience a rock differently, as would a bat through the use of echolocation. The rock then is a iconographic representation of the pattern constructed by our minds. Nonetheless, there is still an objective structure that exists independent of any given individual conscious subject interacting with it. All of reality then is composed of, and contained within, this universal consciousness.

Neutral Monism vs Idealism: What’s the Better Theory?

There are a few reasons I think idealism is favourable over neutral monism:

It is a more parsimonious theory than neutral monism in that there is no need to posit an (usually) unspecified underlying substance, nor does it rely on mind and matter being dual-aspect.

It has better answers to the combination problem because it starts with the assumption that everything is fundamentally one, and that individual subjects or objects are simply aspects of a greater whole (although as a former cosmopsychist, I still affirmed this some sense).

Although its not necessarily the case (as I have argued with lots of people in my comments sections), objects, and by extension, the universe, do at least seem to be contingent. By my lights, idealism offers a better explanation of this by prioritising the mind.

It can better account for the intelligibility and apparent teleology of the universe, as everything is grounded in a rational mind.

It avoids any problems with theories of emergence.

It can better account for the mystical and theistic traditions in that it affirms an infinite ground of reality that transcends the material universe.

None of this is a slam dunk against neutral monism, which I still believe is a perfectly rational and coherent metaphysical theory of mind. That being said, given the available data, I think idealism is a moderately better theory that neutral monism.

The Inescapable Reality of Subjectivity

What idealism entails is a sharp distinction between what we could call ontological vs phenomenological reality.2 Ontological reality is what a lot of people mean when they speak about “objective” reality. It is reality as it actually exists. I agree that there is a realm of objectivity that is actually out there, that doesn’t rely on any particular subjective experience to exist. This ontological reality has a real existence beyond the realm of any particular subject. What this means is that although there is a truly external world, we have no access to it apart from our own perceiving of it. Thus, whatever objective reality actually looks like, we only have a limited access to it through our subjective filters.

Phenomenological reality on the other hand is reality as experienced through our own particular subjective lenses. This is a reality that we largely construct in our mind, that is full of conceptual distinctions and webs of meaning that are in fact, absent from objective reality. Thus, what we call “real”, is actually a constant conversation between reality itself, and our subjective experience of it. This means that you absolutely, categorically, cannot escape your own subjectivity. You can’t transcend the subject and embody a perspective from nowhere, nor can you speak from a place of objectivity uninfluenced by personal experience.

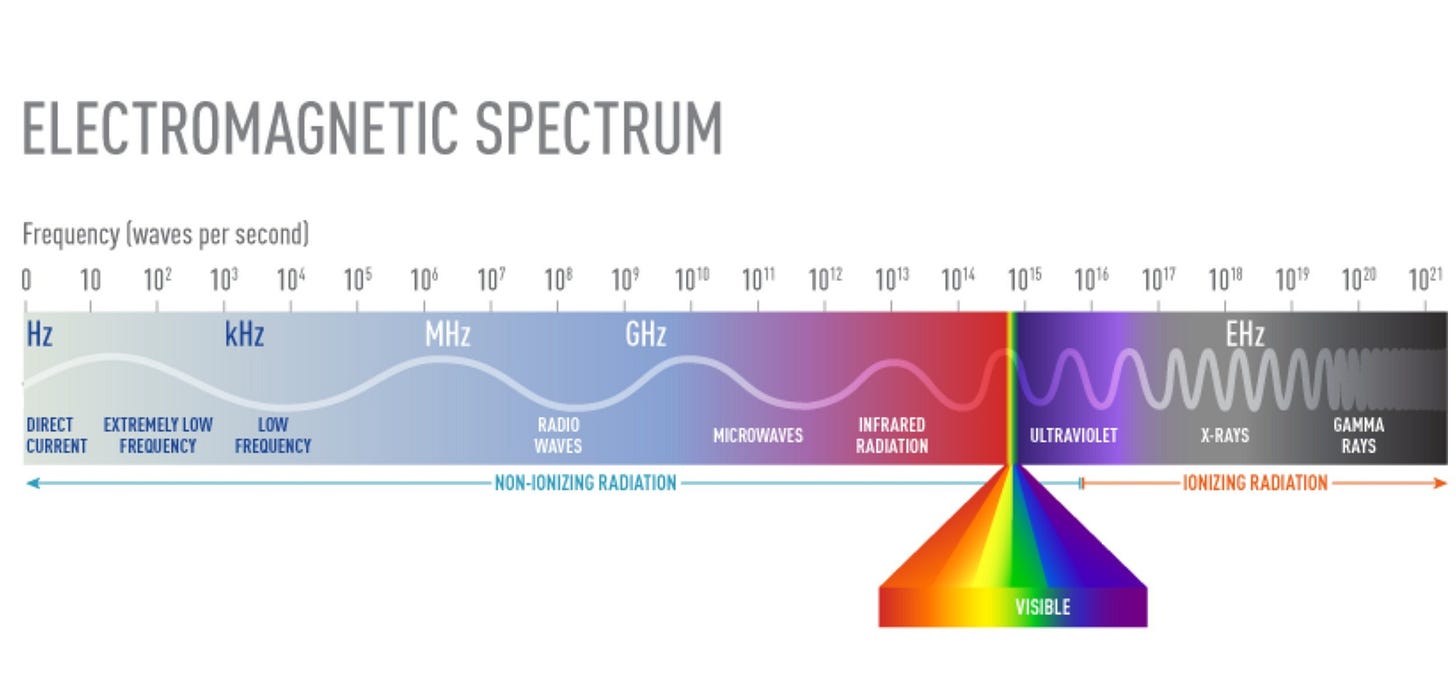

If one doubts this distinction, we only need to consider the magnitude of disagreement between people on the most basic of things. For example, when we argue with our loved ones, our disagreements usually go deeper than opinions or personal values, but often reflect a difference in experience that leads to dichotomous understandings of the facts of the matter. Equally, its well established that eye witness testimony is notoriously shaky due to the wide variety of facts reported when people are asked to recount an event. This is simply because they experience said event in ways that can differ radically. We can also look at empirical data like this diagram, which demonstrates how narrow our perception of the electromagnetic spectrum actually is.

We can also look at what reality is on the fundamental level to recognise that the way we experience reality is incredibly truncated. For example, approximately 99.9999999999996% of an atom is empty space, which means there is significantly more “nothing” than there is something. We don’t experience reality this way however, as it very much appears to us that “space” is filled with observable stuff. We don’t even need to go this deep however. Its trivially true that the average person doesn’t perceive “matter” as a collection of atoms, but as distinct composite objects. Our physical senses are not designed to look at reality on this level and its only possible to do so through the use of technology.

What this means then is reality is made up of an infinite amount of overlapping concentric spheres of subjective experience. We could split this into three main layers; individual subjective reality, inter-subjective reality (what is often called “objective”), and ontological reality (how reality really is). The epistemic implications of this are that as human subjects, the only circle of reality that we have complete and unfiltered access to is our own subjective one. Inter-subjective reality can become increasingly transparent to us through collective integration and synthesis of different perspectives. Ontological reality however will always remain just out of reach, and we can only gesture to and speculate about what it may actually look like.

Conclusion

The search for the nature of reality then is fundamentally a group project. There is no such thing as a singularity of objectivity. All we can do is cautiously approach ontological reality through collective conscious conversation, whilst recognising that the totality of it is always beyond our grasp. Whether we like it or not, reality is grounded in the subject. Ultimately, there is no 1:1 correlation between how reality is, and our perception of it, and if we are going to make any real progress in philosophy, we must accept the ways in which our consciousness constructs reality.

If you are inclined to support me financially, you can become a paid subscriber, or alternatively, you can click the button below to make a one-time donation at ‘Buy Me A Coffee’ (although as a Brit, I prefer tea). Thank you in advance!

This is very similar to my previous cosmopsychist pantheism, but is now something more like idealist panentheism, but more on that in a future article.

A similar distinction is made in critical realism but that is more of a philosophy of science than a broad epistemological theory.

Really enjoyed your work here, Ben! I think it’s very cool to see you exploring some of the same ideas I’ve been thinking and writing about recently. Your whirlpool analogy was also spot-on! I really think it captures the truth of our situation.

Hoping you’ll continue to write and explore more in this vein—I’m keen to see how your journey develops!

(Side note: I genuinely really appreciate how you’re noting the changes in your own beliefs and cataloguing the ideas you’re abandoning/adjusting over time. That’s some real intellectual honesty, and I respect it greatly. You seem to have changed a lot since you first started posting here!)

I think after reading this what would be of benefit for you is to look into not modern cartesian influenced subjectivistic idealism, but rather that of Neo-Platonism or even of Gregory of Nyssa to an extent who in his Hexaemeron speaks of matter as simply the nous or intelligible content of things coming together as bundles of properties to be material. Anyway, the big point is the object and subject divide is ultimately a problem only beginning with Descartes--though influenced by William of Ockham's nominalism. the nominalism of Ockham that universals aren't real but just in our heads, made our consciousness the source of reality. Descartes then splits the res cogitates (thinking thing or mind) from the res extensa (things extended in space) or objects. What this does is fully cut one off from having nature influence one rather we become masters of nature and our own mind becomes perceived as attributing meaning to other things. The idea of a universal consciousness I've always found hard to understand when framed in cartesian terms like this because subjectivity is always subjectivities negotiating a negotiable world always coming into being with some beings (stabilities) and some becoming (change).